We are going to talk about CDI. It is a disease that seemed like it was well covered a decade or two ago, but all of a sudden there is a rush of new information that is clinically important. I would like to review the more recent information.

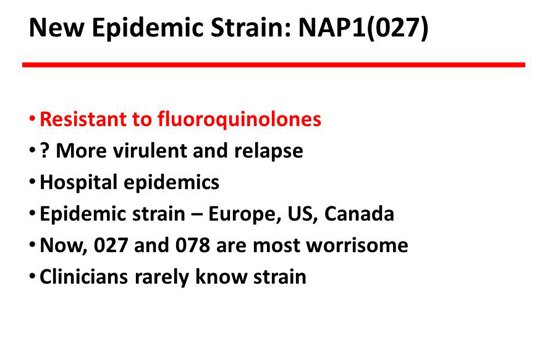

The first thing to acknowledge is that we got a thrust of new cases in the early 2000s in Europe and in North America, including Canada and the United States, reflecting the NAP-1 strain.[1] NAP-1 wasn’t a particularly virulent strain, but it was resistant to fluoroquinolones, and that drove its epidemiology. The slide shows the rush of cases in the United States, a 4- or 5-fold increase over that rather short 8-year period of time.

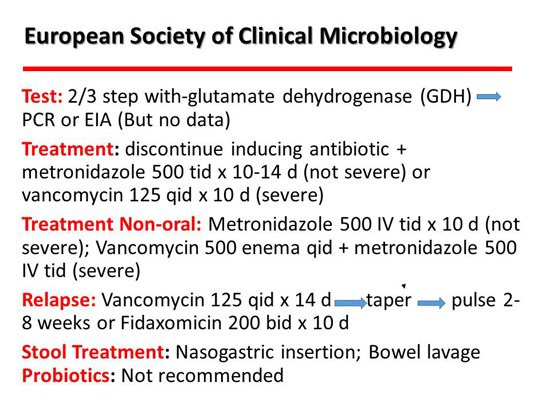

More recently, we received guidelines from the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.[2] I think these are really good. They are similar to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines but much newer — 3 years newer. They said that for mild or not severe disease, metronidazole would be the preferred drug 500 mg 3 times/day, and for severe disease, vancomycin 125 mg 4 times/day. No change there. A helpful hint for the treatment of patients who can’t take oral drugs is intravenous metronidazole combined with vancomycin enemas. For relapse, they like the taper and pulse, which was recommended earlier. It has never been studied but seems to work. The new drug on the block, fidaxomicin, also seems to do well in relapsing disease. Stool transplant is hot, and I will talk more about that. Interestingly, probiotics were not recommended, which is highly controversial. I won’t say much about it except that I don’t personally recommend them, but I don’t mind if my patients take it.

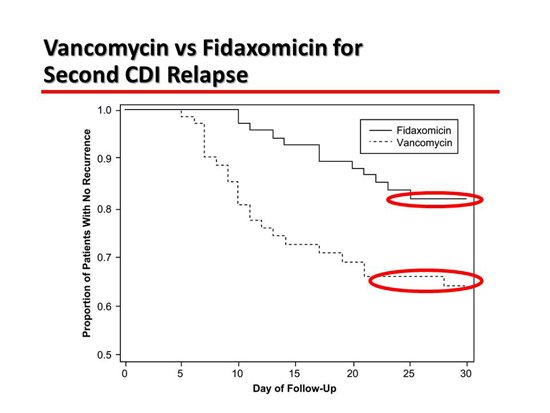

The next slide is about a trial comparing vancomycin with fidaxomicin in patients who have relapsing CDI.[3] Fidaxomicin works just as well as vancomycin for primary disease. It is less likely to prompt a relapse, probably because it has a less profound effect on the colonic microbiome. It re-establishes the pathophysiology that was intended. What it shows here is a difference in relapse rate of 36% vs 20%, which is substantial. That is for relapsing disease.

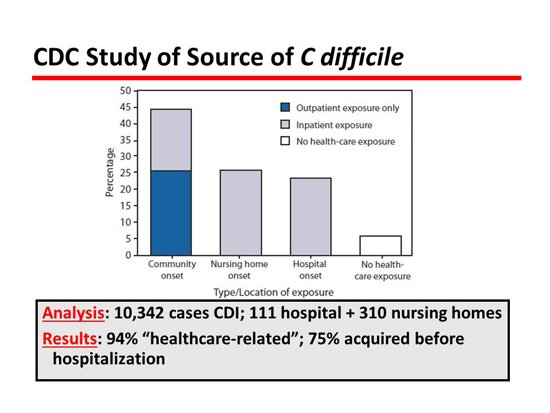

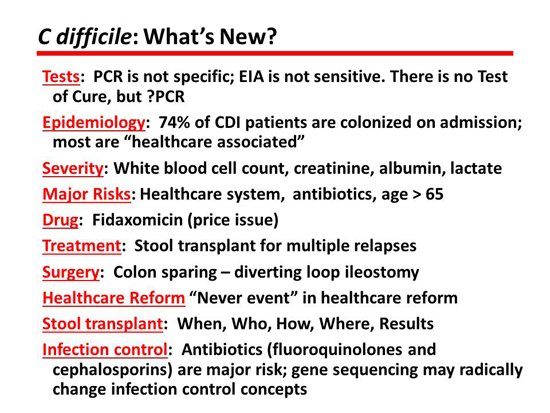

Next is an interesting slide about the epidemiology, which has really changed our concept of epidemiology completely.[4] Most people have always thought that CDI was a hospital-acquired infection, but this great study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reviewed 10,000 cases and showed that only about 25% of patients with CDI acquired the disease in the hospital where it was expressed. Therefore, the majority of patients came into the hospital with CDI, which obviously has big implications in regard to infection control. The patient who comes in with it has to be protected from getting it with antibiotic control and also has to protect others from contagion, which is not the way it has been advocated.

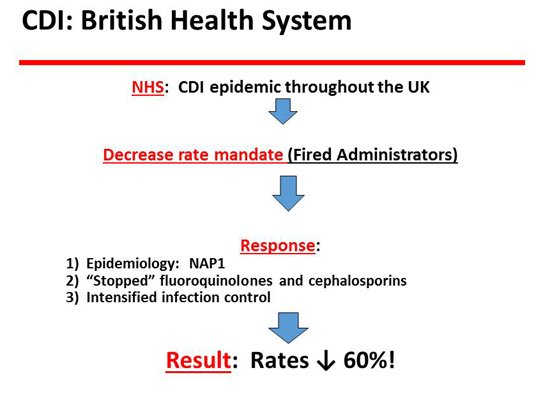

The next slide is the British system.[5] They are running away with this disease especially in terms of the epidemiology of the disease. The UK had a lot of CDI with the NAP1 strain, and the hospitals were told to get rid of it. They were very aggressive in dealing with their epidemic of CDI and, in fact, managed to accomplish a 61% decrease in CDI rates. They did that largely by the control of antibiotics, primarily fluoroquinolones. They essentially stopped fluoroquinolones and also had a major reduction in the use of cephalosporins, the 2 big contenders. Of course, clindamycin is in that mix, but it was not prominently used at the time, so that didn’t make a big difference. But they achieved a decrease in CDI rates, and the reason was that they controlled antibiotics.

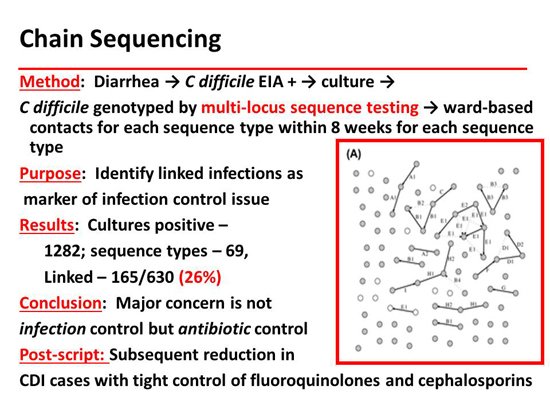

One of the things they have done magnificently is chain sequencing to show epidemiologic patterns. The next slide shows that they were able to demonstrate patient-to-patient transmission within a ward in only 23% of the cases. Chain sequencing is probably the ultimate infection control tool. This has contributed to our changing concepts of the epidemiology of C difficile. Many patients are already colonized when they are hospitalized. That reverses the standard teaching that you get CDI when you go to a ward that has the disease.

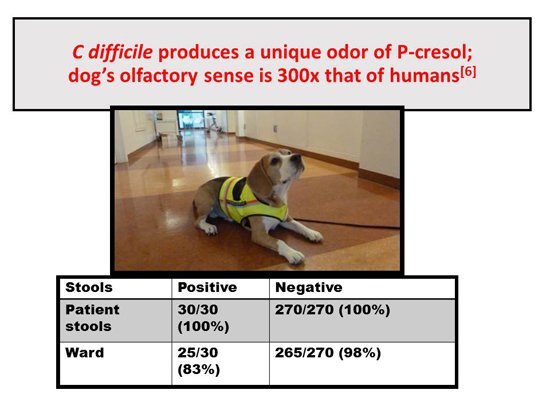

The next slide is not clinically important, but it’s fun to talk about The Netherlands beagle.[6] Of course, dogs have an incredible sense of smell. The dog was trained to smell p-cresol so that it can make an identification of CDI. Its performance was essentially 100% in detecting positives and negatives. I contacted the author to find out what they were doing now with the dog, and they said that they only take the dog on the ward, but they do it regularly. The reason they don’t do it in individual cases is that they simply don’t have enough cases in the lab. So they screen wards, not individual patients, with the dog test, but they still use it. Interestingly, they wanted to bring it to the United States because we have a lot of CDI and it would be a good way to test the dog in the lab, but the requirements for quarantine and so forth were too tough.

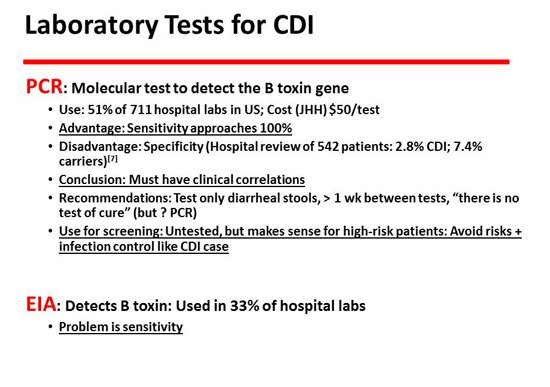

The next slide has to do with polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR is probably the most commonly used test. It is a molecular test, so it is essentially 100% sensitive but not very specific.[7] There will be many more carriers than there are cases, so you have to make clinical correlations in order to properly understand that test. The other test, of course, is the enzyme immunoassay (EIA), which is commonly used in about 30% of laboratories. It has the opposite lesion, which is that it is more specific but less sensitive. It is not a molecular test and is probably not adequately sensitive to detect about a third of cases.

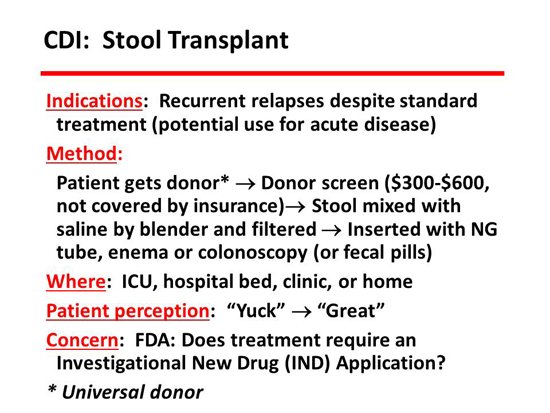

Stool transplant is hot. It has been done since 1958 and has been in a large number of series. What is important here is the summary of late information with guidelines from the IDSA and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), who are now into this in a big way. According to the IDSA, the indications for stool transplant are relapsing CDI 3 times or more. They also advocated for acute disease, but the published experience for that is not very robust — good, but not very robust. The stool that is transplanted can be put in in a hospital, in a clinic, or at the patient’s home. It can be put in by the patient. The method can be by endoscopy, by enema, by nasogastric tube, or by any other way that you can get it there, such as capsules. The important thing is to get the stool into the colon. How you get it there is probably not terribly important. Who selects the donor? We usually have the patient select a donor, but there are other places that use alternative systems. There are several other sources now, including a website operated by medical students called OpenBiome which will send you a stool for $250. You have to be aware that the screening test for a stool transplant costs about $600, and no insurance or third-party payer will pay for this. It is a patient expense that patients need to be warned about.

In terms of clinical management, I’ve summarized a lot of data here. The risks are well known: advanced age, antibiotics (especially fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins), and exposure to the healthcare system. That was the message from before. In other words, the patient acquired the disease not at the current hospital but often from a previous hospitalization, a nursing home where they were previously a resident, or an outpatient clinic. They acquired it in the healthcare system but not necessarily this hospital at this time.

Know the test. The first question to ask when somebody says that there is a positive test for a patient is “which test?” If it’s PCR, worry about false positives. If it’s an EIA, worry about false negatives.

For determining the prognosis, the signs to watch for are shown here. Renal function, white blood cell count, lactate level, and albumin level are all barometers for the severity of disease. Of course, there are also the issues of ileus, toxic megacolon, and so forth.

I’ve talked about epidemiology quite a bit. We call it “hospital-associated C difficile” and not “hospital-acquired” for the reasons that I mentioned. There is no new information about treatment except that fidaxomicin is the new kid on the block. It’s probably the best drug, but it’s also very expensive. For stool transplants, be aware that many of the people watching this will not do stool transplants. What you need to do is know someone in your community to whom you can refer patients if there is an indication, preferably a place that has a fair amount of experience. Also be aware that there are published guidelines on when to do it. For the first time, the FDA has gotten engaged, and now they call stool a drug. You have to jump through some hoops. You have to get a treatment investigational new drug (IND) application. They have some rules about knowing who the donor is or the donor source. All of that can be sorted out at the site of the transplant, but it’s probably a good idea to keep that in mind when you’re communicating with patients.

Those are my highlights for what is going on in the field of C difficile today.

C diff: An Update From the Expert. Medscape. May 20, 2014.